With permission from Dr. Maribel Vann

This 49-year-old patient is an interesting example of what can happen when a rigid connection is made between the two halves of the maxilla. About 20 years before she was first seen by Dr. Vann she was involved in an automobile accident in which she lost all four maxillary incisors. These were eventually replaced with a fixed prosthesis anchored on the maxillary canines (see Fig. 1).

The p-a radiograph in Fig. 2 below shows the framework of the dental prosthesis. Following her accident, she began to develop headaches in the sub-occipital region, partly triggered by biting hard foods. These continued to worsen.

She also developed herniation of several intervertebral discs and finally Harrington rods were placed from C3 to C6 vertebrae (see Fig. 3). The goal was to stabilize the vertebrae in the hope of controlling her neck pain and headaches. Unfortunately, this surgery did not relieve her symptoms.

She was seen at Dr. Vann’s office two years after the surgery. She had continued to deteriorate and was now experiencing a serious disturbance of her vision, causing great difficulty in focusing and reading. She was not able to lift her head up as a result of the vertebral fusion and was conscious of increasing difficulties in chewing.

I recommended separation of the maxillary prosthesis in the midline (see Fig. 4). As the final cut was made through the prosthesis the patient experienced an immediate release of symptoms. The pain around the prosthesis disappeared and there was a tremendous sense of lightness over the whole head. The headaches were subsequently relieved, but the most striking feature was an immediate and lasting improvement in her vision.

Drawing conclusions from one case, no matter how dramatic, carries the risk of misinterpretation. However, once the concept of rhythmic movement of the cranium throughout life is understood, restoring mobility to the facial and cranial structures made good sense.

My observation after many years of practice is that problems caused by the rigidity of the maxilla due to some form of dental device are not unusual. In prosthetic dentistry, the use of rigid devices crossing the maxillary midline is commonplace. For many patients, a rigid device may not pose any problem. However, by asking the right questions—questions that anticipate the device’s potential effects—the practitioner can form a more subtle and comprehensive diagnosis. Even the insertion of a cast removable partial denture can trigger a reaction by restricting the physiological movement of the maxilla.

In orthodontics, there is a strong probability of loss of maxillary flexibility when fixed appliances are being worn, especially a fixed palatal expansion device. In children, this may be tolerated without discomfort but in adults the placement of this type of device may set off a reaction either in the mouth or elsewhere in the head and neck. Fixed retainers on the incisors also may introduce rigidity, but this can be offset to some extent with a flexible type of wire and is therefore not so likely to lock up maxillary movement. A routine question for an osteopath is whether their patient has a dental device such as a fixed upper retainer which could limit physiological movement of the cranium and the body as a whole.

The point is that awareness of other health procedures should be standard in obtaining a dental history.

Gavin

Postscript: The following diagram accompanies a comment below from a dental colleague in Boston.

How do you fabricate a full upper denture without a rigid base? Is there a material you recommend for denture fabrication or do you make your denture in two halfs? I hear dentists doing this but how does it stay in during the day?? DO you have any suggestions. THank you for all your great insight. Patricia

Reprinted from email

Hi Gavin,

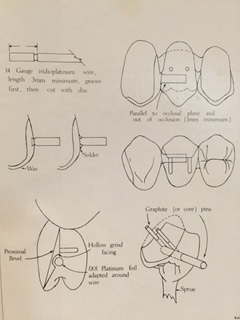

There is a device (procedure) used in Fixed Prosthodontics which could have helped this patient by allowing the support (here provided by the solder joint at the mid-line).

It’s called a Nonrigid sub-occlusal connector. (Guyer, Samuel E., Nonrigid sub-occlusal connector for fixed partial dentures. J. Prosth. Dent. Vol. 26, No. 4. Pages 433-436, October 1971.) It consists of a Pt/Ir wire (about 14 gauge) extending from one crown or pontic in this case into a sleeve in the approximating pontic. Here’s an illustration from the article: (see blog postscript).

Although this article was written for use with a partial coverage posterior bridge and at a time when porcelain fused to gold was in its toddler-hood (note the accommodation [“Graphite [or core] pins”] for a long-pin [porcelain] facing as well as the 14 gauge wire connector), the device (procedure) does seem to fill the need for relief from and possible recognition of rhythmic movement of the cranium.

Perhaps if the dentist had included such a nonrigid sub-occlusal connector between 08 and 09 there would have been no headaches or other symptoms or neck surgery or vision impairment.

Thank you for your kind consideration and Best Regards

Les

I remember Gerry Smith developing a precision attachment about 20 or 25 years ago for fixed prosthodontics crossing a suture to allow cranial motion. Don’t know what became of it. Dentures made from Flexite seem to have worked well for the few cases I have done over the years.