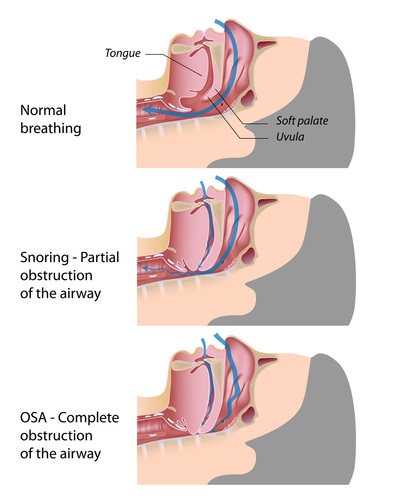

Airway disorders—especially Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)—are increasingly of interest to the dental profession. The use of an oral orthotic of is now accepted as a possible alternative to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in which a mask encloses the nose and mouth and forced-air is used to maintain breathing. From a patient’s viewpoint, an intraoral appliance is less cumbersome, less intrusive and often as successful as the extra-oral machine. There is increasing awareness that our profession can help, with growing numbers of dentists now involved in the treatment of airway disorders such as snoring and OSA.

In contrast to the recent interest in OSA in adults, airway problems in children have been studied for many years in both the medical and dental literature. The “adenoid facies” and the dental picture that often accompanies it was first described almost a century ago. Regarding the pros and cons of removing tonsils and adenoids, there have been massive shifts in opinion over the years, from removal being widely recommended, to its rarely being suggested. Current opinion leans towards a conservative approach unless there have been repeated problems such as chronic inner ear infection due to blockage of the Eustachian tubes. Another useful step is the release of the tongue-tie, giving the tongue the mobility it needs.

When osteopathic factors are taken into the equation, there are three cranial strain patterns; hyperflexion, hyperextension, and superior vertical. All three strains are characterized by distal and superior displacement of the maxilla with its subsequent encroachment on the posterior airway. Even an inferior vertical strain displacement, which predisposes to an Angle Class 11 div i malocclusion, can have distal placement of the maxilla. In both the hyperextension and inferior vertical strains, the maxilla is also constricted laterally, with a high narrow palate, further reducing the nasal airway.

Another potential contributing factor in airway disorders, which to my knowledge is not discussed in the orthodontic literature, has been orthodontic treatment that drives the maxilla distally, either by a high-pull headgear, a neckstrap or by Class 11 elastics. Headgear and neckstraps may now be out of fashion in orthodontics, but they were widely used until about 20 years ago. If headgear and neckstraps have, in fact, aggravated residual airway problems, the dental profession now has an outstanding opportunity to remedy airway problems experienced by many patients who are in their 40s and 50s.

Extraction of bicuspids, which is still common practice, can compound airway problems by causing a reduction of tongue space, forcing the tongue to adapt by encroaching on the posterior airway. It would interesting to set up a protocol to compare former orthodontic patients who received this form of treatment with a matched group who did not. With so many variables involved, a large sample would be required.

Diagnosis of sleep disorders has justifiably become a specialized branch of medicine and dentistry. With adults, the dental approach to treatment favors oral appliances designed to bring the mandible forward to a degree through various procedures. There is even a do-it-yourself kit that can be purchased through a pharmacy. Mandibular advancement is often successful in giving, at least, partial relief from symptoms such as snoring and the prolonged holding of the breath typical of OSA, but is not the complete answer.

An alternative approach is forward positioning of the maxilla in adults. This is a logical solution since it provides increased airway directly where it is most needed but it requires considerable sustained effort by the patient over time. The maxilla will come forward, especially if osteopathic assistance is available to mobilize the facial and cranial bony components. An integrated approable for these patients. Even a small forward movement of the maxilla appears to give considerable relief.

With children, there is a much better chance of achieving airway improvement with a combination of redirecting mandibular growth plus lateral expansion and forward positioning of the maxilla. John Mew and his followers show striking facial changes as a result of early intervention. I have described in numerous articles and blogs that the body is a self-organizing entity and has extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. The earlier an airway problem can be resolved, the better. Osteopathic evaluation of a newborn should include examination for possible cranial displacements and their correction at that time, if possible.< time, if possible.

There are additional opportunities to avoid later airway problems by establishing a correct suckling pattern as well as by cranial correction of newborns and infants. The smooth transition from an infant’s swallow to a mature adult pattern is crucial for the best possible further airway development. These conservative measures may eliminate the need to remove tonsils and adenoids by creating a biomechanical environment that favors their normal development.

Our opportunities as clinicians to help our patients achieve their best possible level of health means a shift in thinking plus a willingness to support and work with other health disciplines. Dentistry has a remarkable opportunity to become a contributor to health across a broad spectrum of issues. Airway disorders are one of the most important of these.

The various cranial strain patterns are described in the series of articles I co-authored with Dr. Dennis Strokon. These are available through my website.

Gavin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.