The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is certainly the most complex joint in the body, which reflects the joint’s wide range of function. If we look at what happens to the joint over a lifespan there are three phases to consider. They are infancy and early childhood, the fully developed adult joint and finally the joint in old age. Much the most attention has been on the adult joint and how to resolve a malfunction, using a wide spectrum of treatment options. This is understandable but predisposing factors can often be traced back to earlier events. The third phase i.e. the full evolution of TMJ development is not commonly seen in modern populations.

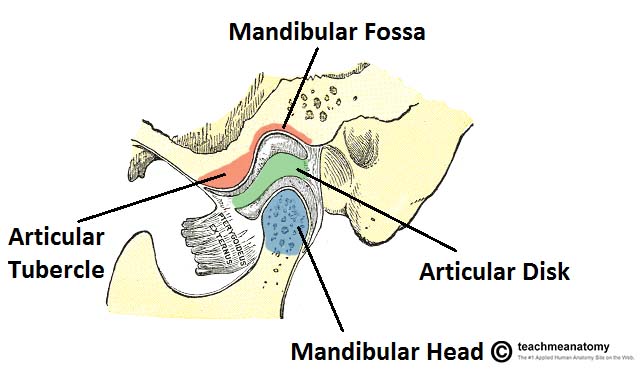

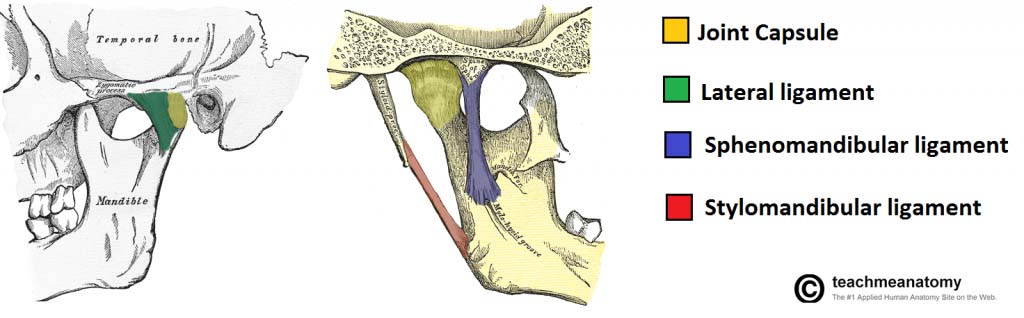

The TM joint has fibrocartilage covering the surfaces of the mandibular condyles, not articular cartilage as in every other joint in the body. This gives the joint considerable capacity to adapt. Another significant feature is the change in shape of the glenoid fossae over time. In the infant, the fossae are just small dents on the underside of the temporal bones. The factor limiting excess movement of the mandibular condyles is the capsular enclosure of the joint. Forward movement of the mandible for suckling is the predominant theme.

The transition from the infant swallow where the tongue fills most of the oral cavity to the mature swallow with the tongue contained by the teeth and the supporting alveolar processes normally takes place between 6 months until 4-5 years. The glenoid fossae deepen to enclose the condyles, the condyles themselves change to adapt to the fossae. Each TM joint is effectively a double joint having two distinct functions, a sliding action and a rotating one with the articular discs serving both aspects. Form really does follow function. Unfortunately in modern populations this transition from the infant pattern may only be partial or may not occur at all,creating the potential for malocclusion to develop.

The last evolutionary stage of the TM joint is not commonly seen in our population but the capacity to reach it is built into the evolutionary potential of the joint. Studies of the skeletal remains of indigenous people such Australian Aboriginals show the effects of long term adaptation. The teeth are severely worn both on the interproximal and occlusal surfaces. When you try to place the dental arches into centric relation, the wear has often been so great that there is no longer a stable centric position. The mandible slides easily in any direction but especially forward as the overbite has been eliminated by wear patterns. In response to this change in function the glenoid fossae have become much more shallow and the condylar articular surfaces have also tended to flatten, allowing greater movement within the joints. From experience with individuals who have had extensive vertical loss of the dentition, the tongue expands laterally, adopting a position between the dental arches to help maintain the vertical dimension.

The orthodontic specialty had the chance to become the prime guardians of the TM joints but has chosen not to do so. However there is a window of opportunity for the specialty to recover lost ground in this area. The real issue over the TMJ and malfunction is not so much the condyle/disc position within the joint but rather the position of the mandible within the stomatognathic system as a whole. It is clear that there is a remarkable ability of the TM joints to adapt. They are designed to do so through a whole series of changing scenarios. Intracapsular disturbance of the TM joints is important but is secondary to the role of the whole mandible and the extensive myofascial system, including the tongue, which surrounds and guides it. Success in establishing the most efficient mandibular position takes priority. Establish this and many of the intracapsular problems diminish and with time may even become minor irregularities of little or no consequence.

Gavin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.