Where do we go from here?

My name is Gavin James and I am an orthodontist in Ontario, Canada. I want to introduce you to ideas about what I believe the future holds for my specialty. Collectively these ideas represent a major change in how to think about orthodontics, a true paradigm shift. Paradigm shifts are not usually comfortable events. They are driven by the need to absorb new knowledge. This often challenges the status quo. My argument is that orthodontists have an opportunity to become major contributors towards achieving good health for our patients. We should not just be concerned about cosmetic improvement, as most people think of when considering orthodontics. We have to take note of advances in other fields of health and how these affect our area of responsibility.

At the moment, the orthodontic specialty is in deep confusion over how best to proceed. The heart of the problem, in my opinion, is that a live organism like the body does not function by using commonsense Newtonian mechanics. Quantum mechanics are much closer to how the body actually functions. For many years this has been understood by scientists in other fields. This directly affects the assumptions on which current orthodontics is based. This article is, therefore, a reassessment of these ideas.

In 1961, Prigogine, a physicist and Nobel Prize winner, described a live organism as " a non-linear, complex, dynamic, self-organizing system, far from equilibrium." This definition is now widely accepted in biology. One important characteristic of such a system is extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. This means that a small adjustment introduced early in development will cause a much larger reaction than the same force introduced later. This is a powerful argument for early treatment but there is an additional factor to consider. An organism can "choose" its response to an external or internal stimulus. Any force being applied should, therefore, be biocompatible, if possible. Otherwise, it may suppress the body's innate ability to self-correct. This concept certainly applies to orthodontic intervention. There are several ways to test if an applied force is appropriate for the individual and ensure the most effective response.

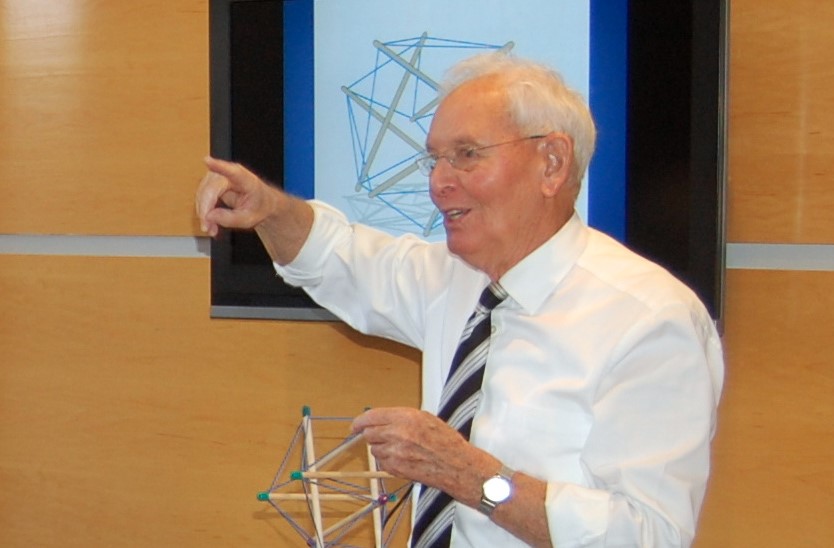

In the 1970s, not long after Prigogine published his findings, the work of Buckminster Fuller became known. He was an architect but also an original thinker, working from first principles. He invented the geodesic dome, a structural form which rapidly became popular as a solution for certain types of construction. He also coined the word tensegrity, an abbreviation of tensional integrity. Ingber, a Harvard biologist, and researcher has investigated Fuller's ideas for many years. His Scientific American article in 1998 is an excellent introduction to tensegrity. Levin, an orthopedic surgeon, has also explored the tensegrity concept. He modified the name to biotensegrity to emphasise that tensegrity principles are found repeatedly throughout nature as well as in the human body. Scarr, an osteopath, has published a recent textbook on the subject. I recommend it as a more comprehensive explanation of tensegrity.

A tensegrity structure consists of continuous tension and interrupted compression. This arrangement creates a balance between the two forces. There is a constant flow of energy through the system. It does not have levers or joints and has been described by Levin as being chaotic, non-linear, complex and unpredictable by its very nature. This description closely resembles that of Prigogine. One feature of a tensegrity structure is that when a force is applied to any part of it, the force is immediately absorbed by the whole organism rather than remain localised. This means that a force such as an orthodontic spring creates a reaction through the whole body. My experience suggests that biotensegrity concepts are basic principles in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment. As far as I know, biotensegrity principles have barely been recognized in orthodontics. It is fascinating to come across such a powerful idea with the potential to create such change.

Given the challenges facing the specialty, there is an urgent need for orthodontists to review what they do and how they do it. It is my belief the specialty has an opportunity to deal successfully with these challenges by seeing them as part of the larger change occurring in all of medicine and dentistry. I have outlined two particular aspects which present the argument for a more comprehensive viewpoint. Clinical evidence to support this can be found in my series of articles and blogs published in peer-reviewed journals over the last two decades and are available for free on this web site.

Gavin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.