In my last blog, I showed that distortion of the cranium during birth could be accompanied by distortion of the facial features. Fortunately, as the infant begins to swallow and suckle, the distortion may resolve itself by the action of the tongue, lips and cheeks but this does not always happen. In Europe, pediatricians accept manipulation of the cranium in newborns and infants to resolve such distortions. In North America, typical treatment for a severe cranial distortion in infants may involve a custom-made helmet worn over several months. This is feasible because of the plasticity of the cranium in infants.

Where the distortion is less severe, cranial asymmetry may not even be noticed and may persist throughout childhood and adolescence. I gradually came to realize that many of the facial characteristics I was seeing in my patients were extensions of an underlying cranial distortion. It was time for a fresh look at what I was doing.

One of the benefits of working with other disciplines is exposure to ideas which extend our thinking. Twenty-five years ago I was introduced to a classification of cranial anomalies based on the work of an osteopath, William Sutherland. This has proved to be particularly useful in orthodontics. The classification is built around what happens at the junction of the sphenoid and occipital bones, the sphenobasilar synchondrosis (SBS).

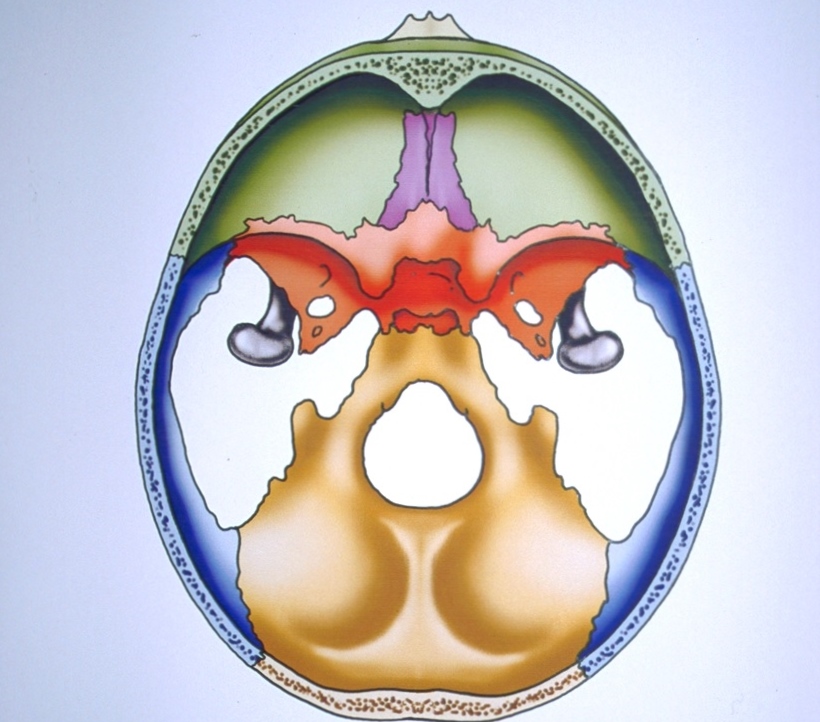

Fig. 1 - Sphenobasilar Synchondrosis is the centre on which the whole cranium pivots.

Figure 1 is a diagram of the cranial base seen from a vertex view. The temporal bones have been left out to improve clarity. As its name implies, the SBS is a cartilaginous suture and does not ossify until around 25 years of age. As various forces come to bear on the exterior of the cranium, the SBS acts as a stress breaker, allowing the two principal bones of the cranial base, the sphenoid and occiput, to adapt at the SBS to these forces. As they adapt, different reactions occur in the interlocking bones.

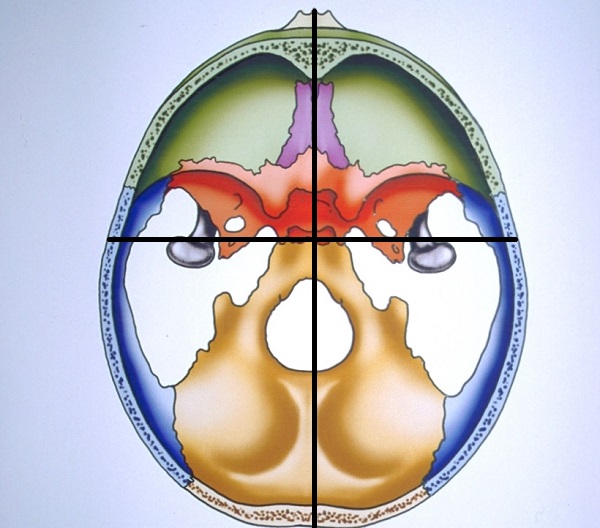

Fig. 2 Each quadrant is described by its relationship to the antero-posterior axis of the cranial base. It is said to be internally rotated when the structures in the quadrant are nearer the mid-line. It is externally rotated when they move away from the mid-line. The quadrants can also displace in an upward or downward direction. These possibilities underlie the huge variation we see in the human face.

The way to understand what happens to the cranium and face is to divide the cranial base into four quadrants (Fig. 2). Each type of cranial strain tends to produce a characteristic displacement of the quadrants. It is possible to gain a much more specific picture of why the face and the dentition in any patient have developed as they have. This leads to more logical and comprehensive treatment planning since it enables the factors underlying a malocclusion to be taken into account.

Gavin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.